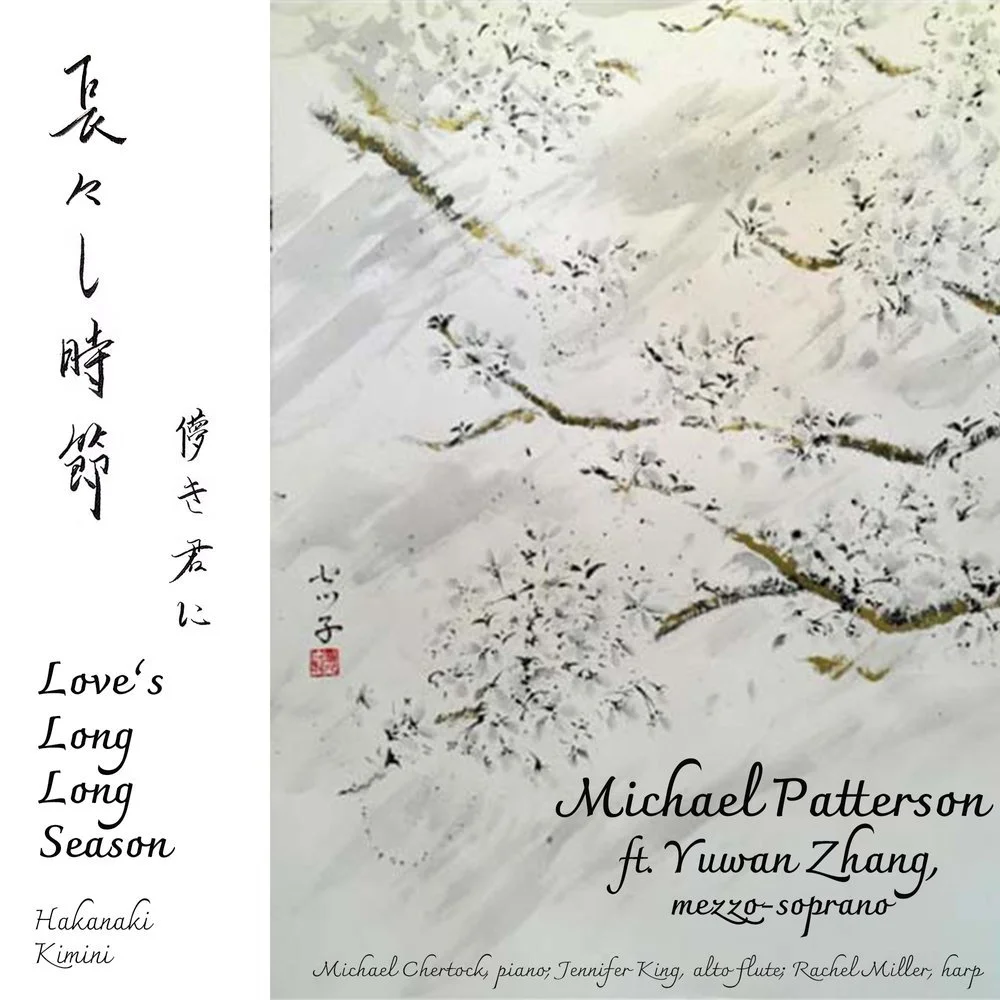

Releasing Date: June 20th, 2024

Composer and Conductor: Michael Patterson

Vocal and Producer: Yuwan Zhang

Piano: Michael Chertock

Alto Flute: Jennifer King

Harp: Rachel Miller

Recording Engineer: Kim Pensyl

Mixing and Mastering Engineer: Chengchao Josh Huang

Painting: Setsuko Lecroix

Cover Calligraphy: Xujia Dai

Japanese Consultant: Hitomi Hiraoka

Notes from the composer:

The song cycle "Love's Long, Long Season" was originally written for piano and voice in 2012. These pieces reflect themes of "unreachable love," encompassing imagery such as autumn leaves, falling snow, plum and cherry blossoms, the moon's phases and seasons, the rustle of leaves, and the sounds of cicadas, frogs, cuckoos, and nightingales. Themes of clandestine meetings with lovers, famous beauty spots, court ceremonies, the quiet of a monk’s hermitage, the deaths of rulers, patrons, and mistresses, and the poem written by the poet on the eve of his death, as described by Rexroth, are also woven into the cycle. Each poem incorporates patterns of dance gestures, creating a rich landscape of images to represent musically.

When I was very young, a Sophomore at the College-Conservatory of Music, one of two books I purchased, independent of my college textbooks, was “A Selection of Poems” by E. E. Cummings. The second was an unusual book titled “The Zen Koan, its History and Use in Rinzai Zen” by Isshu Miura and Ruth Fuller Sasaki, with “Reproductions of Ten Drawings” by Hakuin Ekaku. Both these books were “keystones” and informed my poetic outlook over the years. My interest in the short forms of Japanese Haiku, Zen, and the culture of Japan only increased. Once I began composing music to these beautiful poems from the Japanese, I decided to take on the challenge of setting them in the original language.

The translations in Kenneth Rexroth’s remarkable book, "One Hundred Poems from the Japanese," were brilliant and practical, but I felt that the short phrases would be more aesthetically pleasing in their native language. With this goal in mind, I began consulting many Japanese singers I knew at the Mannes School of Music, where I was teaching, as well as several instrumental artists I was working with in NYC. They provided valuable insights, even pointing out that some phrases in the poems were no longer in use. I also read Rexroth’s meticulously researched introduction, which offered an invaluable historical overview of the origins and practice of singing and speaking the poems. Inspired by Rexroth's and Arthur Waley’s approaches, I decided to attempt my own translations, aiming to capture the essence of the poems rather than settling for word-for-word translations.

The key turning point in creating a performance and recording was to find the right singer who was classically trained, but not overly “operatic. Someone who could sing simply, and yet be expressive. Yuwan Zhang fit that part of my concept. She also added much to the translations since she knew the language well. Finding the artist, pianist, Michael Chertock was a blessing, his musicality and ability to sense what was needed in phrasing and articulation was a great help. The marvelous interpretations by Jennifer King, whose tone I love, made her alto flute sound at times, almost like a bamboo flute, and the graceful and musical playing of harpist Rachel Miller made this the perfect trio to record these pieces.

A personal note of thanks to Kim Pencil, whose perfect sound engineering laid a solid foundation for the mixing. Many thanks to Josh Huang for patiently adjusting the mixes and shaping the final result. And a final personal note of thanks to all who supported this project with your finances and encouragement.

The piano and vocal version of the songs was completed in 2012. The version for piano, harp, alto flute, and mezzo-soprano was completed and recorded in 2024.

- Michael Patterson, 2024

Notes from the vocalist:

It was a pleasure to get to know these beautiful poems and interpret their ancient emotions through my singing. Performing these songs connected me to the past and allowed me to bring the music into the future. I hope my interpretation conveys these timeless scenes to the audience. This is the magic of music: creating a bond that transcends time.

In the first song, according to my research, Emperor Kōkō wrote the lyrics on the seventh day of the lunar new year. Coincidentally, our recording session for the album also took place on the seventh day of the lunar new year in 2024. Everything came full circle. I believe Emperor Kōkō would be delighted and surprised to know that his poem was set to music and recorded many years later on the same day he originally wrote the lyrics.

The essence of Japanese art lies in its indirect interpretation of "love" and "longing" through various media. Their love is seen in the moon's gaze, their loneliness in the autumn air, their tranquility in the snowy ground, their resolution in the river’s wave, and their hopes in the new sprouts. The key is the subtlety and the journey of the audience, or the Aite (相手), to discover these meanings for themselves. Thus, this album is named “長々し時節,” the ancient poetic way of writing “The Long Long Seasons”. The pronunciation of “長々し”, “naga naga shi”, could also be written as “長流し”, and that changes the title meaning to be “The Long Flowing Season”, which matches the heart of waiting for the beloved ones. These songs and poems are like letters, with the subtitle “儚き君に,” which means “To the Unreachable You.”

This album selection offers diverse perspectives, spanning from emperors to monks and men to women, capturing a wide range of emotions about attachment to others. Researching the details in ancient Japanese was an enjoyable journey, allowing me to learn about the culture and interpretive methods that were previously unfamiliar to me. These poems embody the essence of their time and culture.

While singing the first song, I was thinking of the green of the sprouts and the white of the snow. I saw a person walking alone in a distant field, and as the scene zoomed in, I noticed them crouched down, searching for green to pick while the snow gradually fell. In the second song, I interpreted the changes in Lady Kasa’s inner life by imagining myself on an ancient, quiet night, suddenly waking from a dream, and reflecting on grimness, gentleness, and resolution. I aimed to create a balance between tenderness and fear, as this song conveys the true feeling of unrequited love (片思い). She regards her beloved as the sword she holds, but she can no longer distinguish between dream and reality, leading to a mixture of happiness and sadness. In the third song, I placed myself in Monk Ryozen’s perspective. I saw the dusk painting the autumn mountains red and gold and felt the loneliness of my life repeating every day. I want to find a way out but don't want to break the peacefulness. Perhaps I have already grown accustomed to it.

In the fourth song, the tenderness reveals that it is from a woman’s perspective. The lyricist, the Attendant to Empress Koka, uses a metaphor to compare brief love to the cut roots of reeds in the Naniwa River (難波江). She employs the term “ひとよ” (一夜, a night) to highlight the brevity of the cut roots of the reed. The last word, “わたる” (wataru), is understood today as “to cross” and written as “渡る,” but in this poem’s context, it could be interpreted as “long and flowing.” While singing, I reflected on the feeling of being unable to let go and looking back, which then transformed into devotion and resolution. In the last song, I aimed to convey the contrast between concealment and the subtle fear and surprise of being seen, capturing the heart-skipping moment of inner emotional fluctuation while maintaining calm on my face.

I also found out that in the fourth song, the original meaning of “みをつくし” (miotsukushi, 澪標) referred to markers used in the river, and it was famous in the Naniwa River. Today, Osaka City uses Miotsukushi as the symbol of the city, as it has a place called Namba (難波, same spelling but different pronunciation), and the real Naniwa River is nearby. In ancient poetry, "みをつくし" was used to mean "devotion," similar to its use in the fourth song, where it is written as “身を尽くし” (same pronunciation but meaning “devotion” based on the characters).